Author: Chris Wood

From a market standpoint, as opposed to a geopolitical one, there has so far been remarkably little fallout from recent events in the Middle East.

That said, one consequence is that it makes it much harder for the widely anticipated deal between Saudi Arabia and Israel to be concluded.

Saudi has not recognised Israel since it was established in 1948.

On that point, an article in a recent Economist noted that Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman (MBS) did little to hide his “relish” at the prospect of such a strategic pact in a recent rare TV interview with Fox News given just prior to the Hamas attack on Israel on 7 October.

In the interview he gave on 20 September, MBS said that such a deal would be “the biggest historical deal since the Cold War” (see The Economist article: “Trip hazards”, 30 September 2023).

Such an outcome would now seem extremely hard to conclude in the foreseeable future given the passions aroused on the Arab street.

The same Economist article also noted that only 2% of young Saudis support normalisation of relations with Israel, according to the 2023 Arab Youth Survey, compared with 75% in the United Arab Emirates which did normalise relations with Israel in September 2020.

Indeed, beyond the fact that the Hamas incursion into Israel occurred on the almost 50th anniversary of the 1973 Yom Kippur War, the other obvious motivating factor would have been precisely to block such a deal.

Still it remains very clear that MBS does not want the Palestinian issue to disrupt in any way his ambitious plans to diversify the Saudi economy away from its dependence on fossil fuels.

In this respect, it was noteworthy that the annual Future Investment Initiative conference, also known as the “Davos in the Desert”, went ahead on schedule between 24-26 October or only 17 days after the Hamas attack.

Meanwhile, recent years have seen a big improvement in relations between Saudi and India, as reflected in the summit between MBS and Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi in Delhi after the conclusion of the G20 Summit in September.

In many respects, these two leaders stand out globally for their efforts to drive growth in their respective countries.

As regards India, the long-term case for investing in Indian equities remains compelling.

The long-term growth potential can be highlighted again by a few key data points.

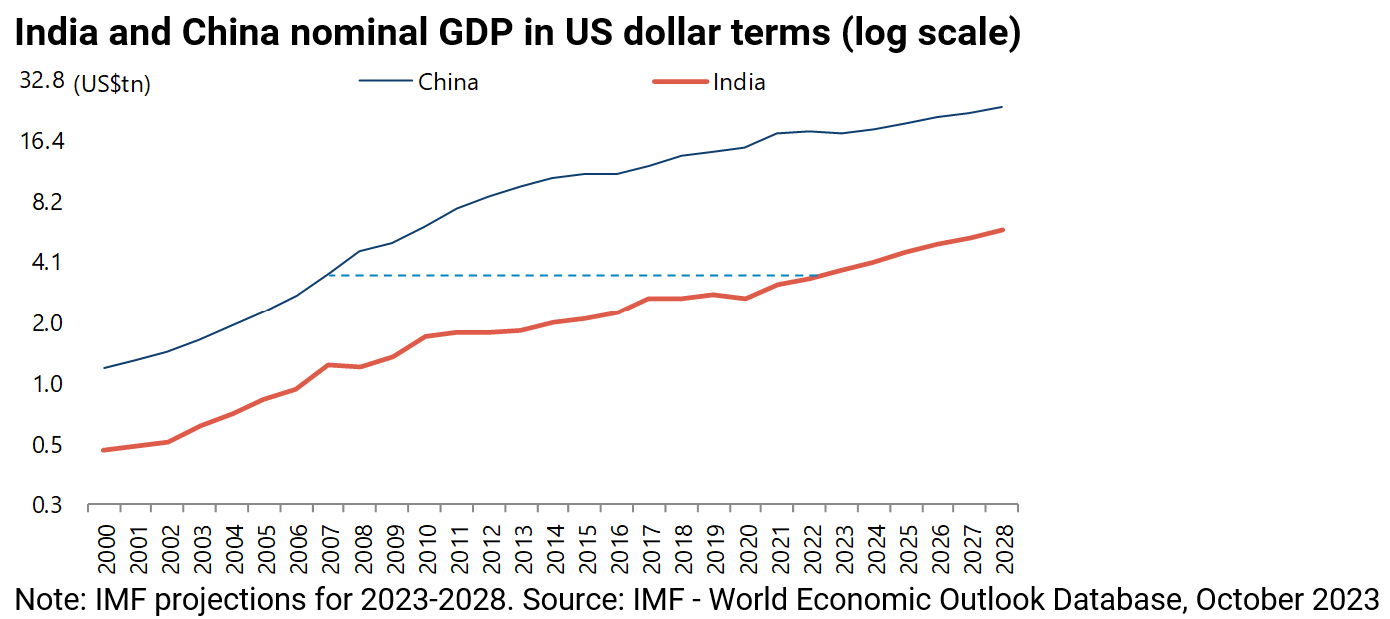

Thus, based on a far-from-aggressive projection of 6.3% annualised real GDP growth for the next five years, as forecast by the IMF, India could become the world’s third largest economy by 2027, surpassing Japan and Germany.

By way of context, India’s GDP today is near where China’s was in 2007.

India’s nominal GDP was US$3.39tn in 2022, compared with China’s US$3.56tn in 2007.

The IMF now projects that India’s nominal GDP will grow to US$5.43tn in 2027, with real GDP rising by an annualised 6.3% in the five years to 2027, based on the latest estimates published in October.

This compares with a projected nominal GDP of US$4.87tn for Japan and US$5.33tn for Germany.

While America’s and China’s GDP are projected to reach US$31.4tn and US$22.3tn respectively by 2027.

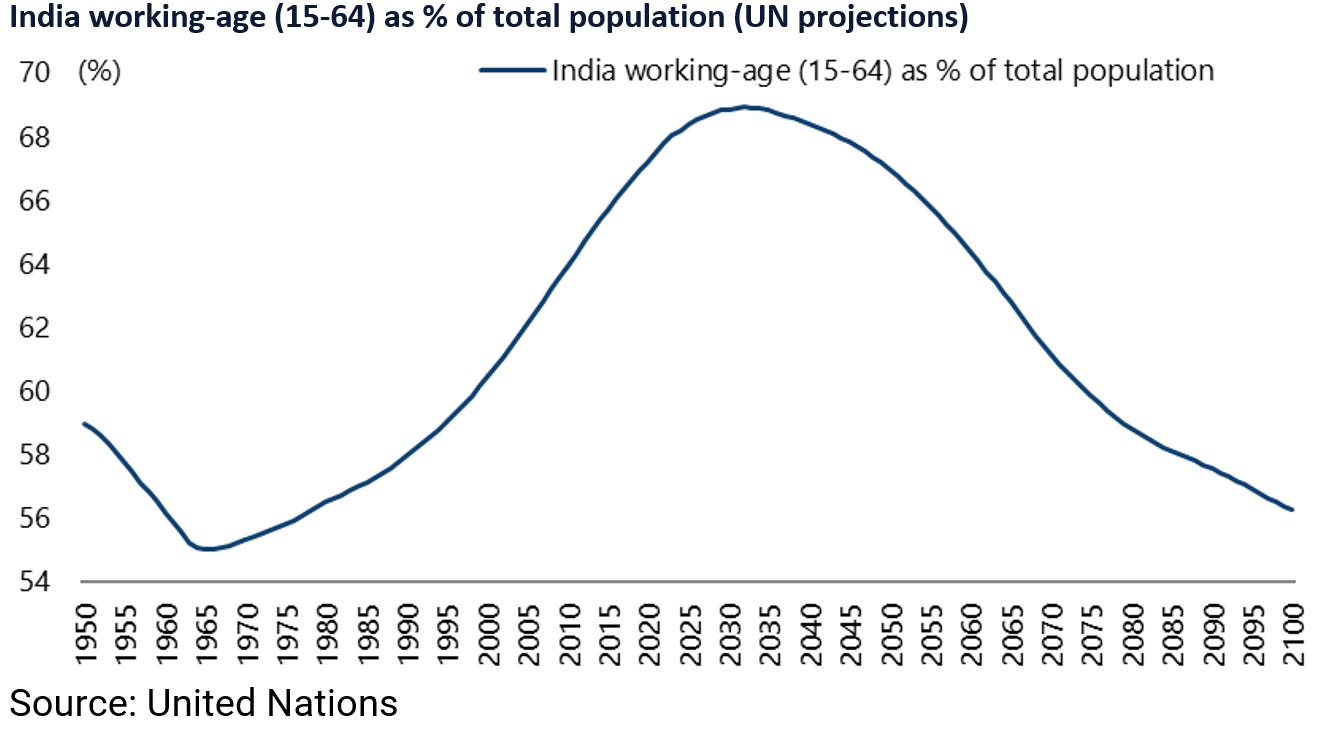

This forecast is in the context of India’s still-improving demographics.

India’s working-age population (aged 15-64) now accounts for 68% of the total population and is projected by the United Nations to peak at 68.9% in 2032

But India’s story is about much more than just positive demographics.

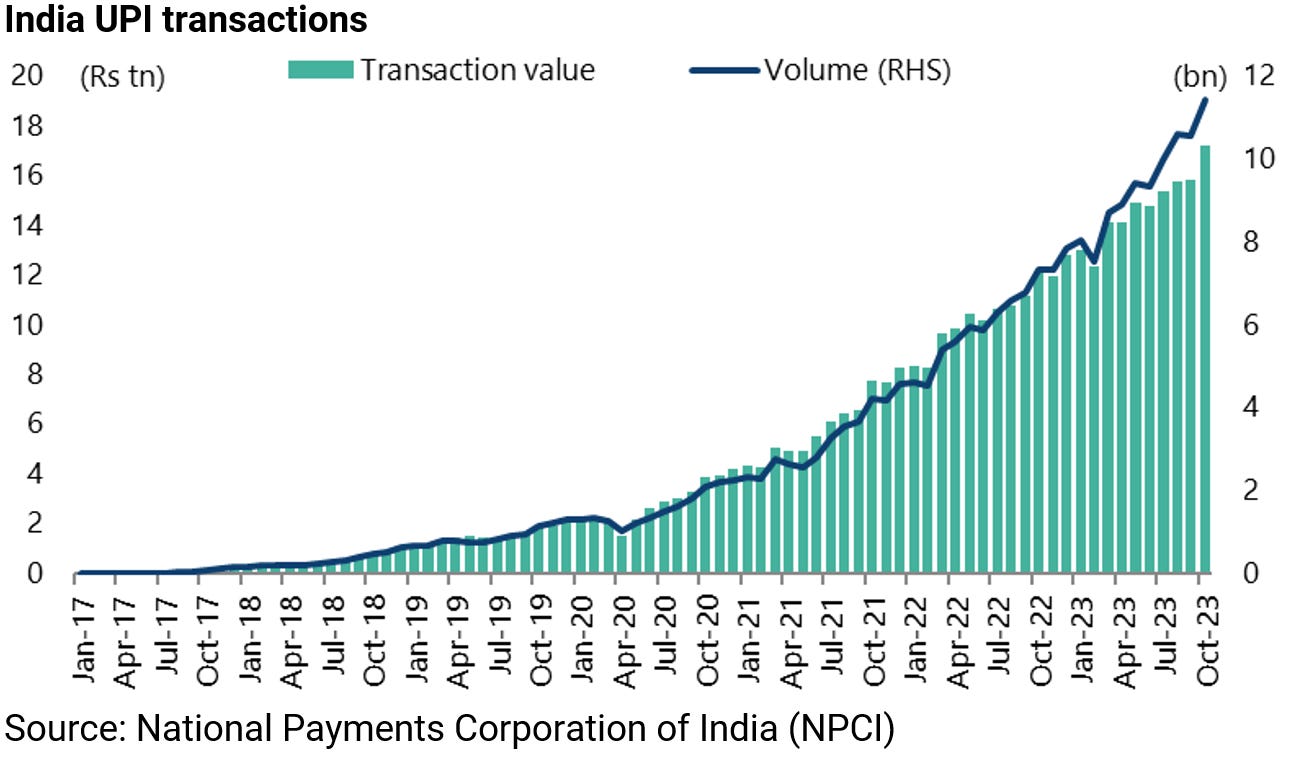

The growth outlook is also enabled by India’s arguably unique digital infrastructure, as reflected in the Aadhaar electronic ID card and the related massively successful Unified Payments Interface (UPI) where transactions are now running at Rs17tn (US$204bn) monthly.

There is also the huge upgrading of physical infrastructure since Modi came to power in 2014.

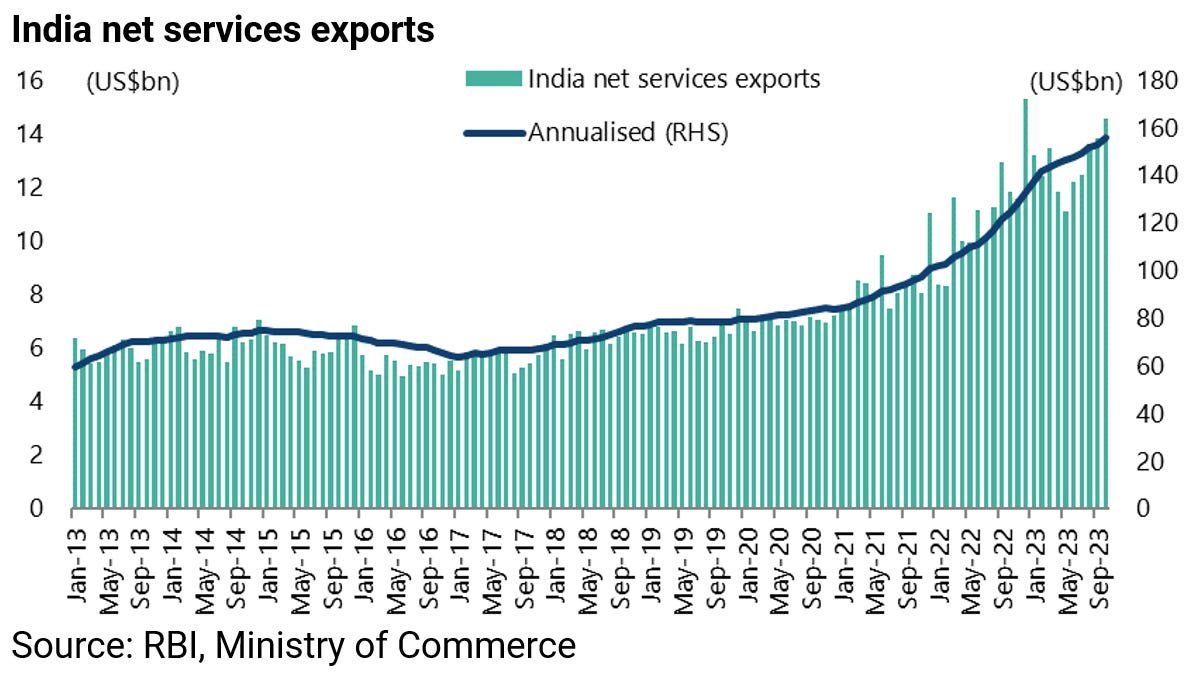

Meanwhile, if India remains primarily a domestic demand-driven story, the country’s export potential should also not be forgotten.

The longstanding success story has been IT exports.

But recent years have seen a surge in service sector exports, in addition to IT services.

Thus, net exports of services have risen from US$84bn in 2020 to an annualised US$156bn in October 2023.

One aspect of this is the growth in so-called “global capability centres” (GCCs) where multinationals base their global IT operations out of India.

Revenues from this area are now US$46bn compared with US$195bn for IT services.

So, this is an area where globalisation is definitely not yet in retreat.

There is also the obvious potential for India to attract foreign direct investment in manufacturing as multinationals from Apple down seek to diversify their production away from China to hedge escalating geopolitical tensions.

In this respect, India’s big comparative advantage relative to other alternative destinations in Asia is that it will offer access to the next big domestic consumer market after China.

Meanwhile, the IMF’s base case of 6.3% growth for the next five years seems in some respects conservative if Modi can be elected for a third five-year term in the general election due to be held next April-May, as now seems likely.

On that point, Arvind Panagariya, a former vice-chairman of the Indian government think-tank National Institution for Transforming India (NITI Aayog), in a book published last year to highlight Modi’s achievements in his first two terms in power (see book “Modi@20 Dreams Meet Delivery”, Rupa Publications, 14 April 2022), forecast 8% annual real GDP growth in the post-Covid era based on “mutually reinforcing reforms of labour laws, bankruptcy system, corporate profit tax and indirect taxes, complemented by rapid expansion of infrastructure and digitization”.

The above projection seems not so far-fetched, with the big risk political continuity.

The result is that India’s growth potential remains hard to exaggerate, most particularly relative to other countries.

This is why, if the recent positive trends are maintained, India can account for a significant percentage of global growth in the next 10 to 20 years.